There are multiple lenses through which to view our blurry relationship to objects. What one considers subject and object is blurred. For example, because I understand my self as an “I” (a subjective knower), I also understand my self as “me” (an object that is known). Objects are made out of stuff, and I’m made out of stuff. There’s a sense in which human bodies are leading ourselves towards inorganic indeterminacy. We are dying and we will turn into inorganic stuff. So maybe there’s an underlying connection between “me” and the inorganic in objects.

No-thing or no-one lives in a vacuum. I experience both the external phenomena in the world, as well as all of my internal phenomena. But maybe this distinction between “inside” and “outside” phenomena is incorrect. Because my body is essentially inter-corporeal; I have microorganisms (which are foreign bodies) living inside of me. My self is a compound of human and non human parts. I’m a porous assemblage that likes to refer to myself as “me.”

Hearts, 2021

(3) 30 Second Voice Sound Recorder Modules for Plush Toys

And this “me” (or do I mean to say “I”?) has a desire to interrogate the boundaries of self. It seems to me the single self is a legend. The human psyche is made of components, and functions more like a family of selves rather than a singular individual. Increasingly the distinction between myself as an individual and myself as part of a collective feels blurred. I can sometimes feel myself being influenced by shadowy technological entities to act in synchronicity with crowds (for example: the recent mass political action taken in the streets as well as online). So on an individual level, I’ve been wondering if certain selves can’t be shared among others?

Illustration from “STALKING THE WILD PENDULUM: On The Mechanics of Consciousness” by Itzhak Bentov, 1977

In the movie Cast Away (2000), Wilson the volleyball serves as Chuck Noland’s (played by Tom Hanks) personified friend and only companion during the four years that Noland spends alone on a deserted island. Named after the volleyball’s manufacturer, Wilson Sporting Goods, the character was created by screenwriter William Broyles Jr. And from a screenwriting point of view, Wilson serves to realistically allow dialogue to take place in a one-person-only situation.

I imagine Chuck Noland sitting on his raft looking at Wilson floating away and screaming, “You are an object that serves a function, there are expectations that you provide joy to some and profit others who let you get pushed around. I am a part of the problem. I am looking at your disposition through a human-centric lens. I freed you from your original function yet I assigned you a new function, that of companion, a role you never asked for.”

At the time of the film’s release, Wilson launched its own joint promotion centered on the fact that one of its products was “co-starring” with Tom Hanks. Wilson manufactured a volleyball with a reproduction of the bloodied handprint face on one side. Despite the object being mass produced, upon purchasing two of the replicas, I notice each handprint has a unique quality to it.

Two Wilsons, 2021

Two Wilsons, 2021

(2) Cast Away volleyballs. 8”x8”x8”.

Affordances have been defined as potential actions that objects and other entities allow for. For example, a handle affords gripping, just like a doorknob affords twisting or a button affords pressing. Perceived objects automatically potentiate afforded action. Object affordances also facilitate perception of such objects, and this occurrence is known as the affordance effect.... Object affordances can thus shape actions for the active perception of the object of interest.1

Object sexuality is a form of sexual or romantic attraction focused on objects. People who experience this attraction may have strong feelings of love and commitment to certain objects. Most media’s initial impulse seemingly is to try to pathologize the people who express object sexuality. I’m more interested in the ways in which these people are preternaturally attuned with objects.

Agnieszka Piotrowska, Married to the Eiffel Tower, 2008.

TRT: 09:43. Re-edited by Andy Bennett, 2021.

“People can love objects, but they love them to a certain degree. More or less for practical purposes. That’s why they don’t see the soul of the object. Whereas when you truly, truly, are interested in an object, and you’re willing to bear your soul, then you see theirs.”

—Erika Eiffel

The scale of the objects often seem to make them unattainable objects of desire; the ideal union (for the person) will always be out of reach. So the people featured in Married to the Eiffel Tower make models of the objects of their fixation. While not comprised of the “original” material, the models serve as a kind of talisman—one that embodied the spirit of the “original” object. The models scale also enables human dominance over the object.

Eija-Riitta Eklöf-Berliner-Mauer’s model of a section of the Berlin Wall, photo taken by Lars Laumann, 2008.

“Gender doesn’t actually…. obviously you can’t lift up a leg on the Eiffel Tower and see whether she’s male or female, but, I think what it really boils down to is we can’t call the object an “it,” because in the language that we speak, referring to something as an “it” instantly means its inanimate.”

—Erika Eiffel

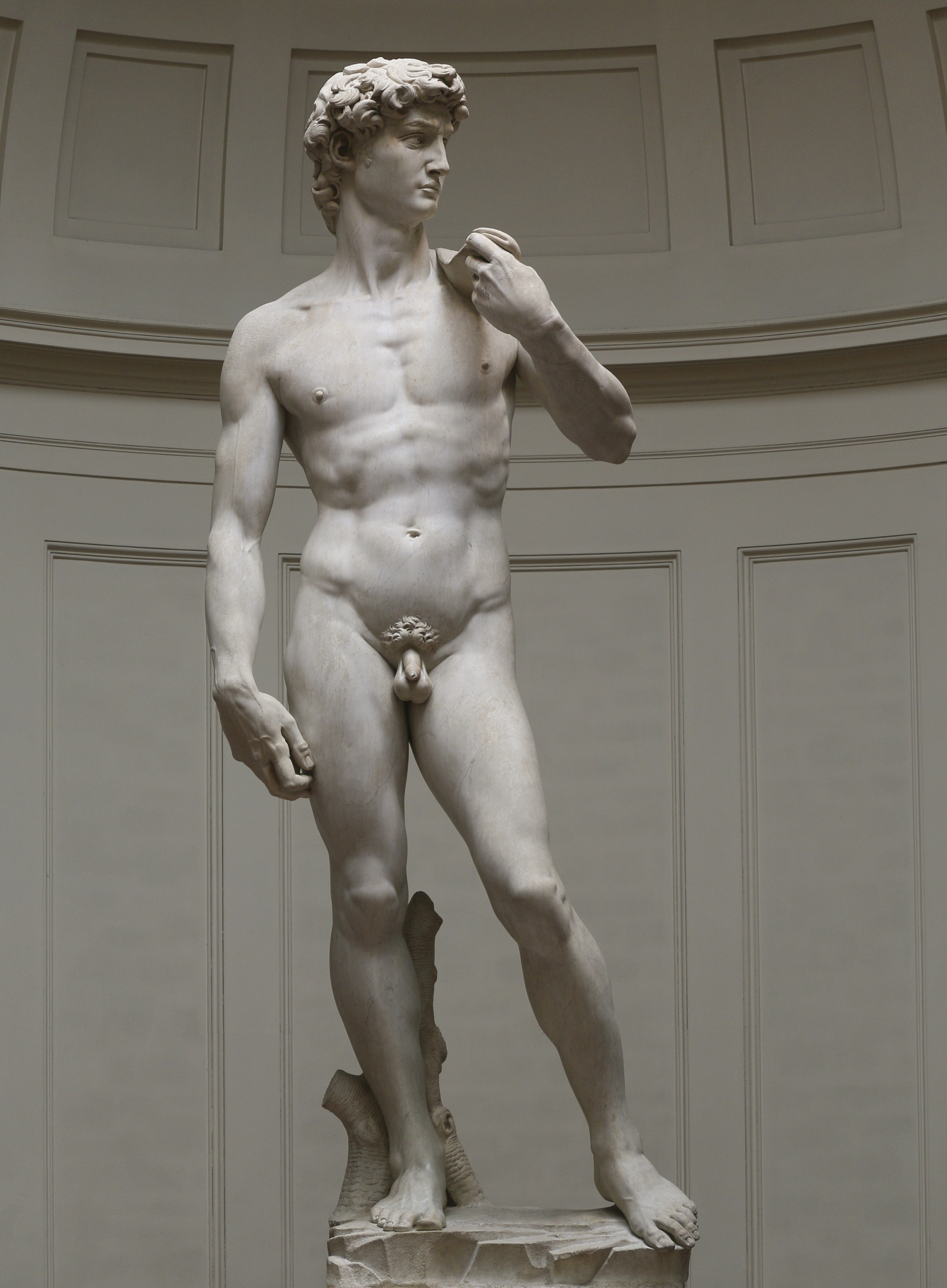

Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504.

Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504. Marble. 517 cm × 199 cm (17 ft × 6.5 ft).

Le Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy.

“I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence, close to the great men whose tombs I had seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty ... I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations ... Everything spoke so vividly to my soul. Ah, if I could only forget. I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call 'nerves'. Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.”

—Stendhal (pseudonym of Marie-Henri Beyle),

Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817).

Although psychologists have long debated whether Stendhal syndrome exists, the apparent effects on some people are severe enough to warrant medical attention. The staff at Florence's Santa Maria Nuova hospital are accustomed to tourists suffering from dizzy spells or disorientation after viewing the statue of David, the artworks of the Uffizi Gallery, and other historic relics of the Tuscan city.

Though there are numerous accounts of people fainting while taking in Florentine art, dating from the early 19th century, the syndrome was only named in 1979, when it was described by Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini, who observed over a hundred similar cases among tourists in Florence. There exists no scientific evidence to define Stendhal syndrome as a specific psychiatric disorder; however, there is evidence that the same cerebral areas involved in emotional responses are activated during exposure to art.

Sandro Botticelli, The Return of Judith to Bethulia, 1472.

Sandro Botticelli, The Return of Judith to Bethulia, 1472.Oil on panel. 31 x 24 cm. Le Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy.

“I picked up…. a book on Botticelli. I turned the pages. [I pause on] ‘Judith.’ My attention was arrested and I gazed in fascination…. at the purplish silk of Judith's pleated bodice and long wind-blown skirts. This was something I had seen…. that very morning…. when I looked down by chance, and went on passionately staring by choice, at my own crossed legs. Those folds in the trousers - what a labyrinth of endlessly significant complexity! And the texture of the gray flannel - how rich, how deeply, mysteriously sumptuous! And here they were again, in Botticelli’s picture…. [My] perception is not limited to what is biologically or socially useful. A little of the knowledge belonging to Mind at Large oozes past the reducing valve of brain and ego, into [my] consciousness. It is a knowledge of the intrinsic significance of every existent…. Draperies are living hieroglyphs that stand in some peculiarly expressive way for the unfathomable mystery of pure being. More even than the chair, though less perhaps than those wholly supernatural flowers, the folds of my gray flannel trousers were charged with “is-ness.” To what they owed this privileged status, I cannot say. Is it, perhaps, because the forms of folded drapery are so strange and dramatic that they catch the eye and in this way force the miraculous fact of sheer existence upon the attention? Who knows? What is important is less the reason for the experience than the experience itself. Poring over Judith's skirts…. I knew that Botticelli - and not Botticelli alone, but many others too-had looked at draperies with the same transfigured and transfiguring eyes as had been mine that morning. They had seen…. the Allness and Infinity of folded cloth and had done their best to render it in paint or stone. Necessarily, of course, without success. For the glory and the wonder of pure existence belong to another order, beyond the Power of even the highest art to express. But in Judith's skirt I could clearly see what, if I had been a painter of genius, I might have made of my old gray flannels. Not much, heaven knows, in comparison with the reality, but enough to delight generation after generation of beholders, enough to make them understand at least a little of the true significance of what, in our pathetic imbecility, we call ‘mere things.’”

—Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception (1953).

Beer Robot, 2021

Beer Robot, 2021Budweiser can, box, robotics kit*

*When activated, this Beer Robot scuttles around making a buzzing sound

The combined weight of all the plastic, bricks, concrete and other things we’ve made in the world outweighs all animals and plants on the planet for the first time. The estimated weight of human-made objects is about one teratonne. For every person in the world, more than their body weight in stuff is now being produced each week. From plastic bottles to the bricks and concretes we use for buildings and roads, the weight of all the things we produce has been doubling every twenty years recently. At the same time, the weight of living things has been falling, mainly due to the loss of plant life in forests and natural spaces. If we continue as we are, by 2040, the weight of all human-made stuff will have almost tripled from 1.1 teratonnes to about three teratonnes. This means humanity is now producing stuff at a rate of more than 30 gigatonnes per year. 2

Plush Man (Dog Toy), 2021

Plush Man (Dog Toy), 2021 Plush toy with squeaker removed

Notes:

1. James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1986).

2. Helen Briggs, Human-made objects to outweigh living things (2020).