Gallery Attendant, 2016-2019

Action

*Gallery Attendant consists of working as a gallery attendant at MOCA.

Gallery Attendant, 2016-2019

Action

*Gallery Attendant consists of working as a gallery attendant at MOCA.

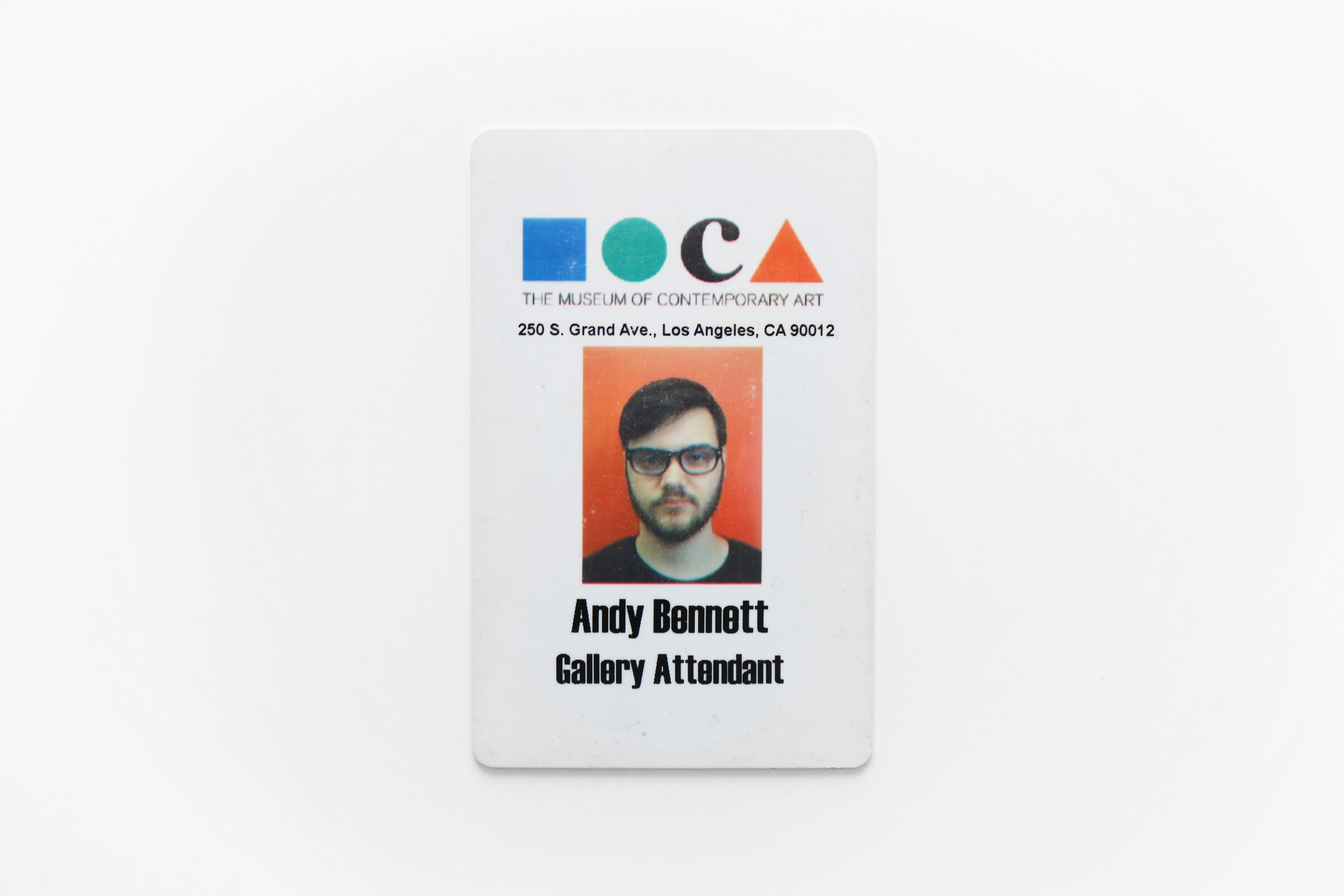

Artifact (Identification) (from Gallery Attendant), 2019

Museum ID

Artifact (Time) (from Gallery Attendant), 2019

Casio watch

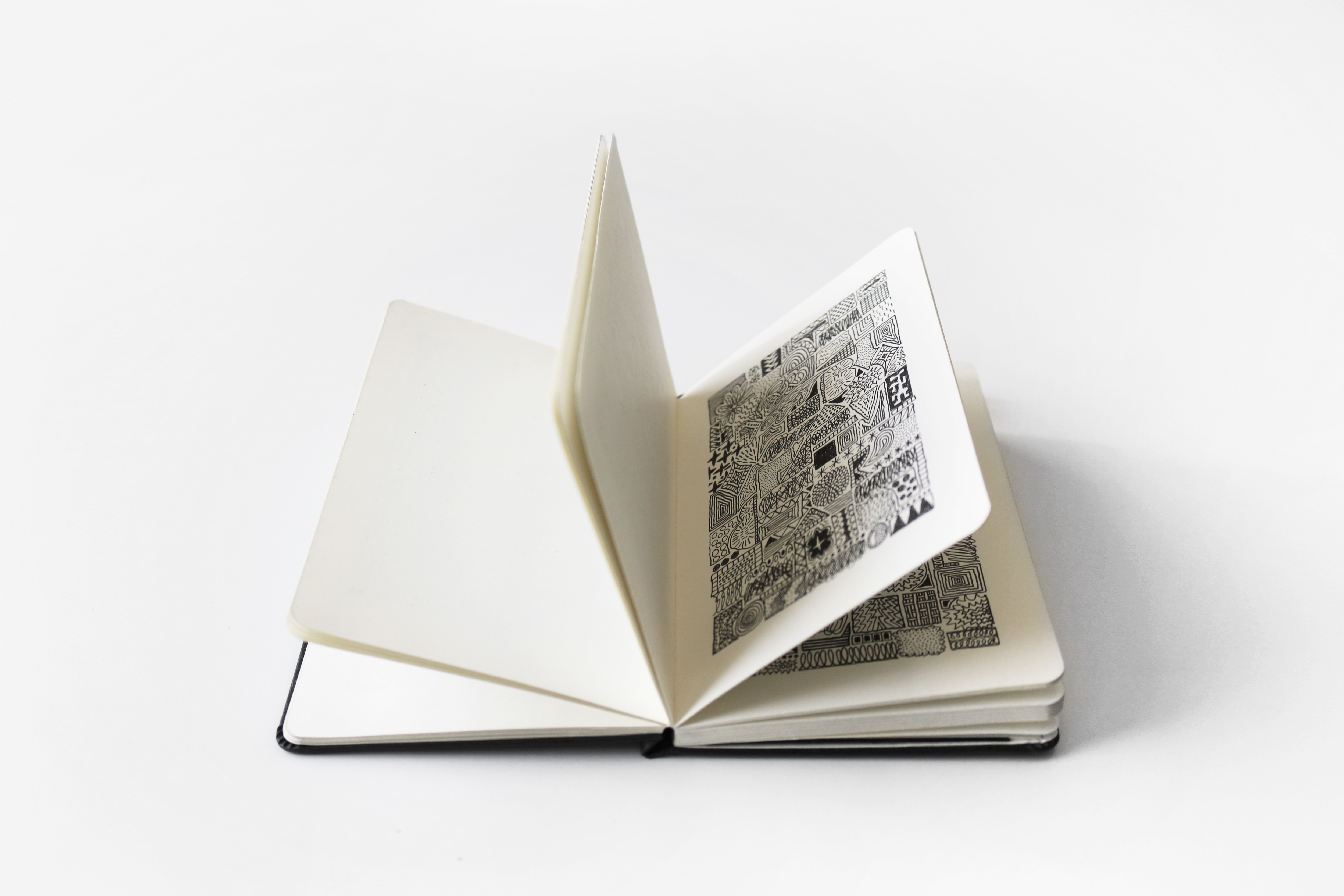

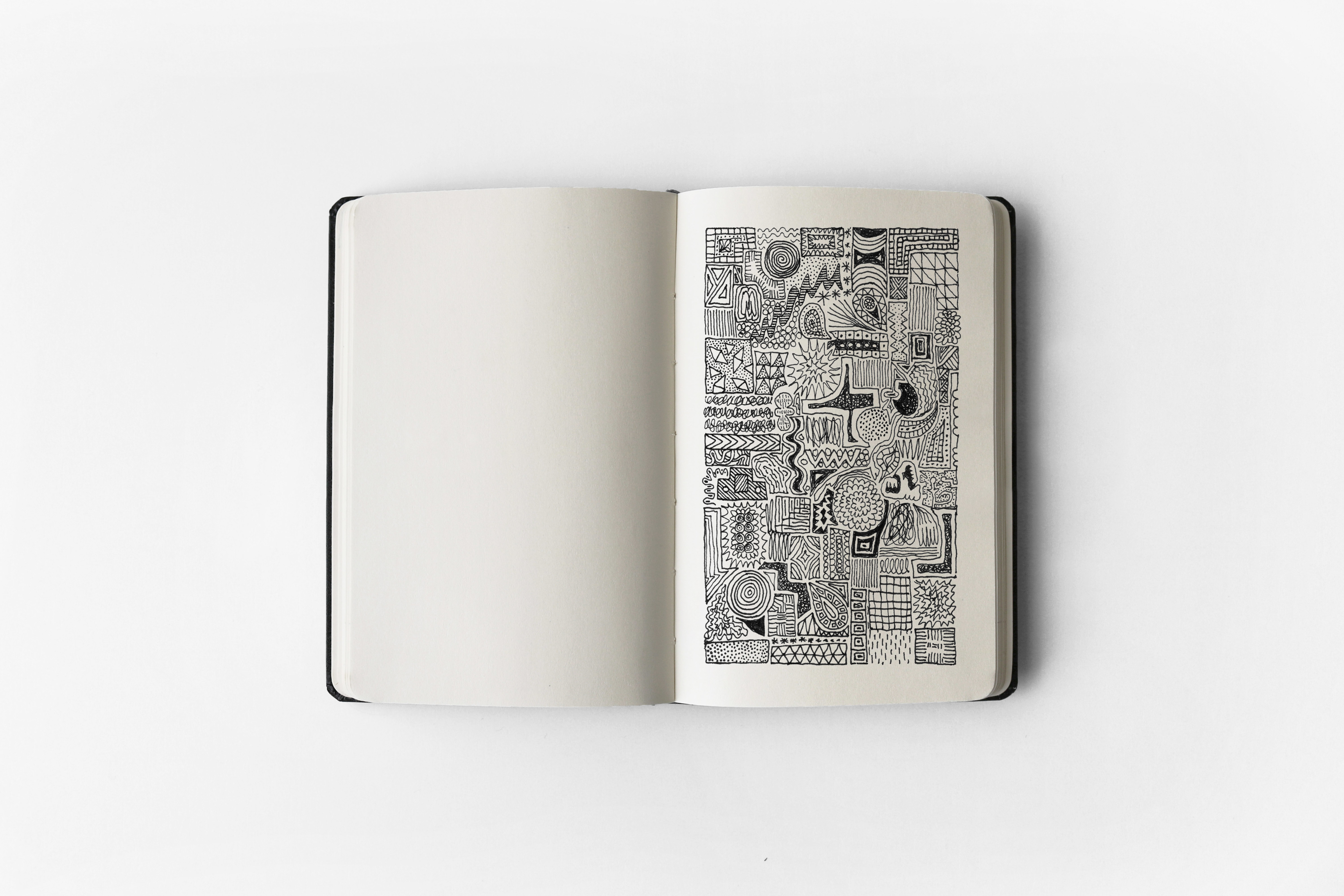

Museum Guard Drawings (from Gallery Attendant), 2019

Book(s) with 100+ drawings

Museum Guard Drawings (from Gallery Attendant), 2019

Book(s) with 100+ drawings

Museum Guard Drawings (from Gallery Attendant), 2019

Book(s) with 100+ drawings

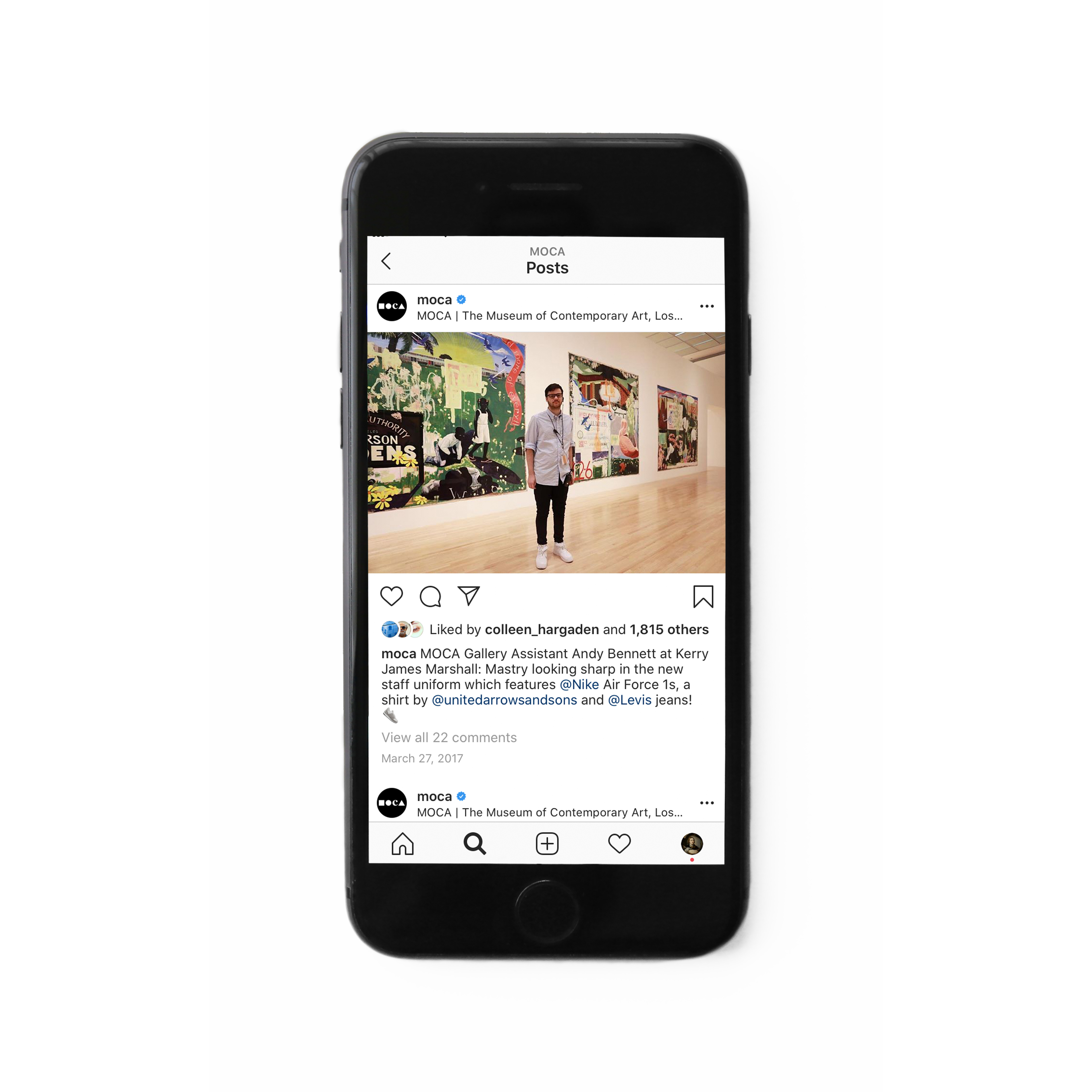

Post from MOCA's Instagram, 2017

Photograph

Pierre Huyghe

(b. 1962, Paris, France; lives in New York)

Shore, 2013

Sanded wall, pigments, and turtle fossil

2015.14

I am standing in the lineage of Jackson Pollock, Sol Lewitt, Dan Flavin, Robert Ryman, Lucy Lippard, Gene Beery, Rober Mangold, Andrea Fraser, Fred Wilson, Wade Guyton, and David Shrigley, all of whom were museum guards. This is my first day on the job. I arrived 40 minutes early, so I got a coffee to waste time. But I don't usually drink coffee and my body is not acclimated to the caffeine. My breathing is short and choppy and my bladder is not sticking to its normal routine. I’ve learned that the way to ask for a bathroom break is to say, “Can I get a 10-100 at post _.” It is not “I need to go 10-100.” I’ve learned that walking 110 times back and forth in front of MOCA’s installation of Pierre Huyghe’s Shore equals about a mile. While walking alongside viewers I imagine that I am joining them on a walk along the shore. A teenage girl enters the gallery. Her face is covered in streaks of eye shadow, which seemingly had washed down her face as she was crying in the recent past and was left intentionally. I found it moving that she’d share that vulnerability so publicly. Had she truly been crying immediately before I saw her? What was the decision to leave it like that? How much of it was strategy? I brush the white dandruff off of my black shirt and drop my tiny pencil on the ground, resulting in a very large noise in the empty gallery.

Thomas Hirschhorn

(b. 1957, Bern, Switzerland; lives in Paris)

Chromatic Fire, 2005

Cardboard, paint, wood, tape, chains, carpet, cloth banner, screws, nails, mannequins parts, wood figurines, electrical wire, printed materials, television monitors, fluorescent light fixtures, wooden beams with nail text, plastic compact disc case, wood log, hammers, drills, and plastic bucket

Gift of Adam Sender

2015.52

I am supposed to warn patrons that Thomas Hirschhorn’s Chromatic Fire contains images of war violence. Decomposing bodies, a decapitated head, and a man’s innards hanging out of his chest are juxtaposed with reproductions of paintings by Emma Kunz, who believed that her work contained miraculous healing properties. “I’m not saying it’s not art,” a man lectures his date in front of a Thomas Hirschhorn. “It’s just not for me. I only like work that makes me happy.” The couple proceeds to hastily walk into the next gallery of abstract paintings from the 50s and 60s. They pause in front of an Agnes Martin, “Ah, I can live with this.” A young man enters the gallery wearing a wrestling shirt. He walks past the bodies of multiple mannequins and small African statues which are penetrated by screws. The back of his shirt had an unattributed quote from Samuel Johnson. “HE WHO MAKES A BEAST OUT OF HIMSELF GETS RID OF THE PAIN OF BEING A MAN.” A Ryobi screw driver sits on the floor. When shown in 2005, it was intended not only to imply, but to enable a viewer to contribute a screw to the artwork. Now that the museum owns the work and it is insured, you are no longer allowed to touch the Ryobi. The insurance company decided it does not constitute as good preservation. “This is so cool.” someone says as they approach the work, camera phone in hand.

John Baldessari

(b. 1931, National City, California; lives in Los Angeles)

I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art

[Wallpaper], 2000/2015

Vinyl

Courtesy of the artist

I am standing next to an iteration of Baldessari’s work I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art when an older woman wearing a black jacket and brown slacks approaches me and asks who the work is by. I say, “John Baldessari.” She gestures towards the wall covered in a large vinyl with the repeated phrase, “I will not make any more boring art.” She smiles, and says, “I discovered him, he had his first three shows at my gallery before leaving me for another.” “What was the name of your gallery?” I ask. “The Molly Barnes Gallery. That’s my name, Molly Barnes.” I smile and ask if he was still making paintings at the time. She says, “He was taking photographs and had started using text.” She smiles and takes a breath before saying, “He did give me one of his paintings when he left the gallery. I used that painting to buy my place in New York, couldn’t have afforded it otherwise.” She chuckles. “His show at the Met had a wall-text that was all about his time at my gallery.” I smile and nod. She asks my name, which I honestly wasn’t expecting. I say, “Andy.” She says it was nice to meet me and then asks, “Can you point me in the direction of the bathroom?” I point her in the direction and she walks away. I’ve been working four days straight and have a bit of a hangover, but I don’t want to drink water here because then I’ll have to take a 10-100, and I hate asking for anything over the Vertex Standard EVX-531 radio clipped to my back pocket. I enjoy saying “10-4” because it feels as though I am affirming the very notion of communication itself. My legs start to wobble and I fall back into the wall I'm standing in front of. The radio knocks into wall and scuffs it. It’s a larger mark than I’d expect it to make.

Robert Morris

(b. 1931, Kansas City, Missouri; lives in New York)

Untitled, 1967 (remade in 2011)

Felt

Promised gift of Chara Schreyer

Robert Morris passed away a month ago, but is still alive on his wall text. As I stand next to the Morris, I think about Schroàdinger’s cat. I look at the draped felt, watching as gravity does its trick. I look down at my body and feel gravity slowly but surely loosening my skin. My black shirt draped over me, covering my fluctuating weight. A young boy quickly approaches the work, his arms outstretched ready to touch. I think about the past tense of the sensation of touching the object but avoid engaging in a “felt” related pun. Weeks later, a registrar finds larva nested in one of the wool strips of the work. As I walk into my assigned post, I see a large empty wall where the Morris used to be, the light still pointed exactly where it was installed. “Infested” was the word used by a higher up employee to describe the state of the work.

Carl Andre

(b. 1935, Quincy, Massachusetts; lives in New York)

Steel-Zinc Dipole (E/W), 1989

Steel and zinc

2000.1A-B

I am standing on top of a Carl Andre sculpture as I write this. The work consists of 2 units, one of which is steel and the other zinc. The units are 18” x 39” and are placed side by side on the floor. “I paid 15 bucks to come in here just to see some wood and tile?!” an older man in a Tommy Bahama shirt and cargo shorts exclaims after walking around the Carl Andre exhibition. I have hit a lull in the day. I check MOCA’s SKME stainless steel back waterproof 9068 Japan Mout 3ATM watch. I try to strike up a conversation with a co-worker who recently was hired. “Are you an artist?” I ask. “What does that even mean anyway?” they respond. “Well, do you make art?” “I haven’t in a while.” A woman in stilettos begins to walk on a 64 unit, zinc square from 1976. Stilettos, shoes that are wet, and skin contact is prohibited in the exhibition. I say nothing. I want to believe that she knows of the allegations against Andre, and that this was an act of subversion against both the man and the institution that allotted him an entire wing of the museum. I say nothing as she clicks and clacks across the work. Without stopping she exits the gallery.